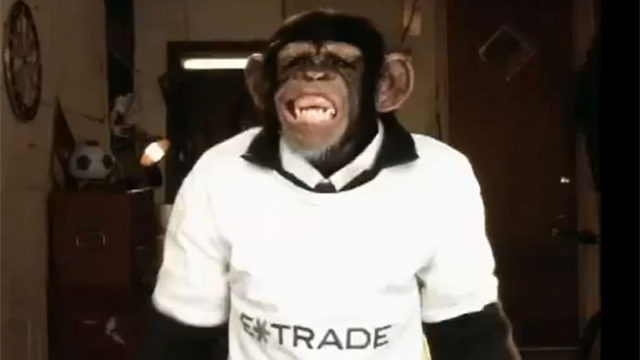

“Money coming out the Wazoo” was the tagline of E-trade’s 2000 Super Bowl XXXIV ad. It was fitting for the time. In the five preceding years, the NASDAQ had risen almost sixfold. However, it was to plummet by 80% in the following months. Of the 11 tech startups that also splurged $2.2 million for a Super Bowl XXXIV ad, 8 had either gone bankrupt or been sold at massive discounts by the next year.

Today’s monumental tech stock rises have made comparisons with the Dot-com bubble unavoidable. 6.2% of U.S stocks have a Price/Sales ratio above 10. That figure has only been higher in March 2000, when it was 6.6%. High multiples are epitomised by Tesla, which added $168 billion to its market cap in the two weeks after its addition to the S&P 500 was announced, despite this adding zero value to the underlying business. The similarly overwhelming enthusiasm for companies with ‘cloud’ or ‘SaaS’ in their descriptions can seem reminiscent of that shown towards those in the 1990s with ‘.com’ in their plan.

Yet there are many important differences between today’s rally and that euphoric period at the turn of the millennium. For one, the federal funds rate was almost 7% in 2000, compared to near 0% today. As Howard Marks explains, this impacts more than just borrowing and saving. Low government bond yields reduce the yield required to entice investors towards riskier assets across the board, leading to a flow of capital into equities. By reducing the required earnings yield demanded by investors on stocks, this directly leads to higher multiples. This is in addition to the price-boosting lowering of the ‘discount rate’, which results from lower interest rates. While earlier than expected tightening of monetary policy would pose a risk, all indications from the Fed point against this happening.

What is more, today’s leaders are superior to those of the Dot-Com bubble. The FAAMG stocks are highly profitable and enjoy a dominant market position. Their growth potential is favourable to alternatives, especially considering value stocks are having their worst run in history (at least since 1826).

Also, high multiples, by themselves, are a poor reason to be dismissive. A few years of high compounded growth easily reduces them to more conventional levels. However, it is still worth asking three basic questions about any prospective investment that you consider to be the ‘future’.

1: Is it really part of the future?

This seemingly obvious question is underassessed in periods of high growth and innovation. As CB Insights shows, the most common reason for startups to fail is a lack of market need for their product. One of those 8 failed startup companies who paid for a Super Bowl XXXIV commercial slot was Epidemic Marketing. $7.6 million of VC funding was lost on its business model, which involved paying customers to attach links to their outgoing mail- essentially manual spam.

The totality of Epidemic’s failure is probably not applicable to many of today’s tech stock high-flyers. Nevertheless, it shows the need to avoid overoptimism about the true extent of potential growth in a market and the risks involved in reaching it.

2: Will it, specifically, be the one to champion that future?

Countless examples show us the importance of this question. Boo.com, a British online clothes store founded in 1998 and Kozmo, a forerunner to Amazon Now, raised $135 million and $280 million, respectively, of VC funds. They were well positioned early on in the e-commerce market. Investors in Blackberry, which once boasted an $80 billion market cap, could point to its edge amongst business consumers and BBM as its ‘moat’. At one point it had a 37% share of the U.S smartphone market. MySpace, once valued above $10 billion, occupied a prime position in social networking.

Prospective investors in these companies could rightly claim that they were investing in the growth sectors of ‘the future’ However, they would have lost all their money if they relied on this reasoning. It is not enough to simply be part of ‘the future’; competition, execution risk, and failure to maintain innovation all must be robustly taken into account.

3: Is the price right?

Unfortunately, even when correctly identifying the leaders in rapidly growing markets, it is impossible to escape the basic rule that price is eventually linked to fundamentals. Cisco and Intel are two exceptionally successful companies. However, to this day, they are still 47% and 37% down on their respective 2000 peaks.

There comes a point when the level of implied future growth from stratospheric multiples needs to be tethered to reality. The fact that Amazon required major unforeseen innovation (e.g AWS) and becoming the fourth largest company in the world to achieve its huge stock price growth over its Dot-com bubble peak (which it took a decade to revisit) suggests it was an exception when considering the importance of price.

Buyer Beware

Today’s market is very different from the Dot-com bubble era’s. Many of today’s upcoming tech stocks will justify their valuations and prove huge winners in ten years time. However, it is worth taking heed of the lessons of history. While we may not be headed for the same dramatic fall as two decades ago, neither the fundamental rules of long-term investing nor human nature have changed; no rally is everlasting and eventually prices must be justified. The year after the NASDAQ collapsed E-Trade was back at Super Bowl XXXV with another ad. Its comparative soberness and new tagline ‘Invest wisely’ clearly illustrate the usefulness of remembering the cautionary tale of the Dot-com Bubble.